20th November 2012

By Bob Appleyard

Seven of us made the journey to Boulby for what turned out to be a fascinating trip. The Boulby mine was sunk in the late 70’s to exploit potash and other mineral deposits, first discovered during oil exploration. The deposits date from the Permian 290-245 million years ago when much of what is now NW Europe was covered by the Zechstein sea. This tropical sea had only a small opening to the wider oceans, resulting in increased salinity and deposition of massive evaporites. In sequence, these are anhydrite (gypsum minus H2O) Halite (rock salt) and potash in the form of Sylvite, KCl. There are also deposits of polyhalides and other minerals. The potash that is mined is combined with Halite and Clay and is known as Sylvinite; to be economically viable the mine geologists search out Sylvinite with 45% potash, about 35% halite and the balance as clay. The potash is extracted by a floatation process at the surface and goes almost entirely to fertiliser.

Up to 50% of the UKs deicing salt comes from Boulby. They could produce more but councils will not order more until it gets very cold, and then it is too late. Ironically, the waste salt and clay are dumped at sea.

The day started well with bacon butties and coffee. After an introduction to the geology, processes and economics of the mine, we were kitted out in day-glow orange shorts and tee shirts, boots, shin pads and helmets. The descent is over 4000 feet and seemed to go very quickly – 15 miles per hour! We then boarded a Ford Transit flat bed with metal cages for 6 on the back and 2 in the cab. The mine covers an area of about 10 km by 6 km in a network of tunnels and ‘roads’ . It is essentially on two levels. The main roads are driven through halite as this is more stable than the sylvinite. Each road ‘out’ for vehicles, men and equipment has a parallel road ‘back’ with a conveyer carrying the sylvinite to the up-shaft. The mine operates 24 hours a day and it wasn’t until 1994 when women were allowed to work underground.

The day started well with bacon butties and coffee. After an introduction to the geology, processes and economics of the mine, we were kitted out in day-glow orange shorts and tee shirts, boots, shin pads and helmets. The descent is over 4000 feet and seemed to go very quickly – 15 miles per hour! We then boarded a Ford Transit flat bed with metal cages for 6 on the back and 2 in the cab. The mine covers an area of about 10 km by 6 km in a network of tunnels and ‘roads’ . It is essentially on two levels. The main roads are driven through halite as this is more stable than the sylvinite. Each road ‘out’ for vehicles, men and equipment has a parallel road ‘back’ with a conveyer carrying the sylvinite to the up-shaft. The mine operates 24 hours a day and it wasn’t until 1994 when women were allowed to work underground.

Mining is done by cutting a ramp up into the overlying potash beds. Prospecting is done by drilling forwards for about 250 metres. Plugs of material are checked for economic amounts of potash. The overlying Carnallitic Marl emits gamma radiation and sensors are sent along the bore holes to ensure that any mining stays 2 metres below the overlying Marl. The actual deposits are not horizontal and what surprised me is that the mine tunnels rise and fall about 2000 feet, following the best deposits. We were in a fairly shallow (and therefore cool) zone at 4000 deep and 35 degrees centigrade. Other areas reach 45 degrees.

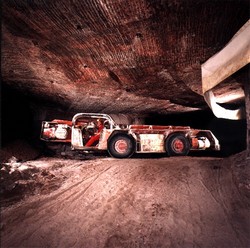

E xtraction is done by large cutting machines, with two rotating drums about the size of a dustbin. The drums have a helix of cutting teeth that draw the material to a central apron where it is gathered and sent along a conveyer to a shuttle vehicle. This works back and forth, taking the material to the end of the fixed conveyers. The cutting machine works a face about 8 metres wide and 3.8 metres high, trending up or down as directed by the geologist. A narrow pillar is left between each face, to give a panel of 55m. The potash in the pillars shears off, so that within 6 months, the pillars look like apple cores. The potash “flows” like magma, and fills any void, so after 5 years, the roof and floor of the tunnels meet! We saw one tunnel where the roof was about 2m above the old floor, so they had to excavate the floor to get vehicles through.

xtraction is done by large cutting machines, with two rotating drums about the size of a dustbin. The drums have a helix of cutting teeth that draw the material to a central apron where it is gathered and sent along a conveyer to a shuttle vehicle. This works back and forth, taking the material to the end of the fixed conveyers. The cutting machine works a face about 8 metres wide and 3.8 metres high, trending up or down as directed by the geologist. A narrow pillar is left between each face, to give a panel of 55m. The potash in the pillars shears off, so that within 6 months, the pillars look like apple cores. The potash “flows” like magma, and fills any void, so after 5 years, the roof and floor of the tunnels meet! We saw one tunnel where the roof was about 2m above the old floor, so they had to excavate the floor to get vehicles through.

The newly created ceiling and walls are pinned to prevent collapse. First, a 6 feet long hole is drilled. Very impressive – it took seconds. Then, a tube of resin and hardener is blown into the hole. Lastly, a huge metal pin is inserted, mixing the resin and hardener which sets solid in ten seconds. This process is happening constantly in what is a very busy, potentially dangerous working environment.

impressive – it took seconds. Then, a tube of resin and hardener is blown into the hole. Lastly, a huge metal pin is inserted, mixing the resin and hardener which sets solid in ten seconds. This process is happening constantly in what is a very busy, potentially dangerous working environment.

Other aspects that we saw were polystyrene air dams, to control the air flow underground, and huge underground workshops. In all, a fascinating day out that pulled together many aspects of theoretical and practical geology. Throughout the planning and on the day, the staff at Boulby were extremely helpful and informative.

The pictures show a rotary cutter and a shuttle vehicle. © ICL Fertilizers. http://www.iclfertilizers.com/Fertilizers/Pages/disclaimer.aspx